I’ve been meaning to, Geraldo. I was waiting for the place to thaw! You provided the impetus for me to do so. But I must say that, compact though this northeasternmost region is —17 individual states are larger than the six states of New England put together — it will take me two postings to even begin to scratch their diverse geography and rich history. Fortunately, New England breaks into two convenient tiers: three states to the south clustered around Boston, and three to the north, packed with trees and moose and offshore lobsters. Let’s look at the lower three this time.

But first, an overview:

Tightly Packed

|

| Rock meets sea on Bailey’s Island, Maine, where we also observe a typical New England lobster shack |

|

| This is the view across a small lake to the town green in Cohasset, Massachusetts. Note the requisite white church |

When Americans moved west in the mid-1800s, it was the New England village model that they copied. And the idealization of New England as a hardscrabble, pastoral haven of feisty individualists, rooted in reality, hasn’t changed much.

That’s why I must confess that it’s not my favorite U.S. destination. While New Englanders are not hostile, they practice wariness, as if they’ve never seen a visitor before. Don’t expect animated tales and flourishing hand gestures, and certainly not hugs. “Nope” and “Ah-yup,” can pass for a New England conversation.

A Veritable New England Gabfest

In fact, one of my cherished tall tales is set there:

Two old Downeasters – or residents of downstate, coastal Maine – are rocking on a porch, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, without saying a word.

After about an hour, one of them points to a far-off tree. “Look there,” he says. “That’s a pileated” – a big, red-crested woodpecker.

The other fellow squints in that direction, shakes his head slightly, and replies, “T’aint.”

Nothing more is said for 15 minutes, as the codgers rock on, back and forth, back and forth.

Finally the first old guy struggles to his feet, stretches, and starts down the stairs.

“Well, got to be goin’,” he says.

“Can’t stand an argument.”

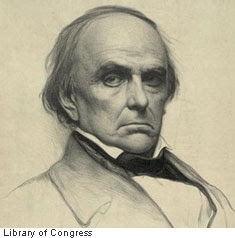

Distinguished Company

|

| Many observers believe that Daniel Webster’s oration in a debate over tariffs in 1830 was the most eloquent speech ever delivered in Congress. Maybe his stern New England stare helped, too |

|

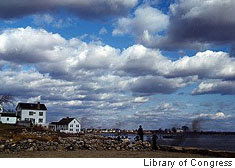

| Beautiful scenes such as this get old after four or five months of New England winter |

Why bother, anyway, if you believe the late American journalist and author John Gunther. He once wrote that New Englanders just “love to be agin’ things.” Agin’ as in “against.”

Quaint and Quirky

But heritage tourists, in particular, go to New England anyway, seeking what’s lacking at home: genuine and abundant history, quirky local color, and plain dress, architecture, and speech. Ask a New Englander if he’s lived there all his life, and he’s likely to answer . . . . “Nope. Not yet.”

Although the region is condensed, it’s a chore to explore. Its cities were built for walking and carriage rides, not the modern automobile. Alien labyrinths in a cornfield are more drivable. Almost all of northern New England’s superhighways, and most of the state roads, too, run north and south, connecting busy Boston with Canada. You can get up and down Vermont and New Hampshire and Maine with alacrity, but it can take forever to go from one of those states to the other.

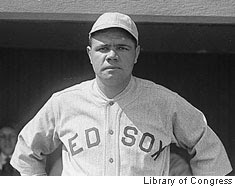

Red Sox Nation

Beantown’s” teams runs as deep as the region’s stubborn streak. The baseball Red Sox, or “Sawks,” as they’re called regionally, have a cultlike following from Connecticut’s capital, Hartford, all the way into Canada’s maritime provinces. I single out Hartford because there are a few misguided New York Yankee fans southwest of there, along the New York border. They must endure the same evil eye that Puritan preachers cast upon the men and women who were branded as “witches” in late 17th-Century Massachusetts and subsequently hanged. And one man was crushed with large stones. Ask a Sawks fanatic, and he – or she – will tell you such treatment is too merciful for a Yankee fan.

Once again so you’re clear: Yankees in New England and Yankee fans in New England are not one in the same.

his army, as “Yankee rabble.” But the rabble were roused. They co-opted the term and applied it to a favorite Revolutionary War song: "Yankee Doodle."

(A brief aside here: In the song, Yankee Doodle goes to town, riding on a pony. Then, of all things, he sticks a feather in his hat “and calls it macaroni.”

Macaroni?

We know that a lot of Italians arrived in Boston a century later, cooking pasta, but there weren’t many around in the 18th Century. Turns out that back then, “macaroni” was a word for fancy Italian clothes. By sticking a feather in his cap, our Yankee Doodle fellow was making a fashion statement.)

One day, and for more than 40 years, a fife version of "Yankee Doodle" would be the Voice of America’s theme song.

Smokestack Cities

|

| Here’s a big mill in Lawrence, Massachusetts, that thrived for a time before closing |

|

| This is the bell tower on the Boott Cotton Mill No. 6 in Lowell. The looms are quiet below, but the National Park Service has turned the mill into a monument to the Industrial Revolution |

not church bells, but those in the belfries of giant mill complexes, which pealed from 4:30 a.m. until evening to signal shift changes and mealtimes. Thousands of people, including young women called “Lowell girls,” aged 14 to 30, left the farms for the mills’ appealing $3.25-a-week wage. But Lowell and Lawrence and other mill towns deteriorated precipitously after World War II as mill owners succumbed to the blandishments of southern promoters who dangled nonunion labor, inexpensive land, ice-free rivers, and tax incentives.

So by 1980, Massachusetts – and other New England places built on the four post-colonial pillars of textiles, paper, boots and shoes, and fishing – were in dire straits.

But along came the “Massachusetts Miracle” of the mid-1980s, when a sudden and simultaneous explosion of the computer and high-tech defense industries and Wall Street-type financial services ignited a boom that drove up employment and tax revenues. Housing prices doubled in many locations.

Then, just as fast in 1988, came a bust. Desktop and personal computers, developed on the West Coast, rendered New England-made mini-computers almost instantly obsolete; the Defense Department began closing bases; and dozens of banks, including the fanatically expanding Bank of New England, simply collapsed.

History and Ecology

|

| Rose Island Lighthouse, off Newport, Rhode Island, is more properly called a light station, since it had a keeper (and family). Visitors can now stay in the keeper’s old bedroom |

Since then, the region has crawled back to life on the shoulders of tourism, biotechnology, higher education, and health services. New England leads the nation in “environmental tourism.” Guests at the Rose Island Lighthouse in Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay, for instance, get quite an ecology lesson. The light station is now a museum and travelers’ hostel where electricity use is strictly monitored, showers are short and chilly, and every guest joins in the daily composting and beach clean-up. “It’s a mind-altering experience without the drugs,” the lighthouse foundation’s executive director told Carol and me when we visited.

|

| Block Island, Rhode Island, is a time warp to slower, frillier days |

|

| In the fall, New England bed-and-breakfast inns are crammed with “leaf peepers,” come to see the autumn glory |

Rhode Island – “Little Rhody” – is smaller than many American cities. Since it was such a haven for people of religions who felt persecuted elsewhere, Italians, Portuguese, French Huguenots, southern blacks, and Jews of many nations settled the tiny colony. The young nation’s most industrialized state early on, it became predominantly ethnic, Catholic, and Democratic in composition.

In the Manner Born

|

| This is the sumptuous dining room of Cornelius Vanderbilt's summer-home dining room in Newport. It was patterned after the Salon of Hercules at Versailles in France |

Newport, but not the rest of Little Rhody, endured New England’s industrial booms and busts quite well. (I doubt that’s true in today’s economic downturn, where much of the evaporated wealth emanated from paper deals rather than mills or fishing fleets or assembly lines.)

Land of Prosperity

|

| The ornate, marble Connecticut capitol in Hartford, with its glittering gold-leaf dome, opened in 1879. It overlooks a 17-hectare park |

|

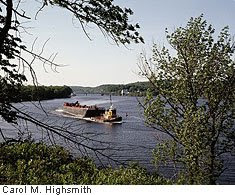

| The narrow Connecticut River Valley forms one of the state’s few richly fertile areas |

In many ways Connecticut has been an American microcosm. The first great Indian wars were fought there. It was in Bridgeport that the nation’s first sewing machine and gramophones were produced, and P.T. Barnum organized his “Greatest Show on Earth” circus and sideshow there during its heyday. Our first agricultural frontier, stretching westward as far as Ohio, was part of Connecticut’s “western reserve.” (My hometown of Cleveland sprouted on land owned by the Connecticut Land Co.) Connecticut never latched onto a memorable symbol like the patriotic “Minuteman” of Massachusetts or the lobster of Maine. But it has become a day-trippers’ paradise, full of quaint inns, out-of-the-way museums, symphony orchestras in six of its cities, and plenty of boating opportunities on Long Island Sound.

Nutmeggers

|

| This enchanting photograph of the Stonington, Connecticut, Harbor was snapped in 1940 |

Connecticut got its nutmeg soubriquet not necessarily because of the nutmeg spice, a precious cargo the state’s sailors used to bring home from trade journeys to Asia. Connecticut Yankees have an especially shrewd reputation in business – so shrewd that it was said they could sell wooden -- meaning phony -- nutmegs to strangers.

There is no such a place as MassConn Island. But the three southern New England states do have a denser, more ethnically diverse, faster-paced character than the three charming, rural states to the north. I’ll give you their story, and my impressions, when we visit “New VerMaine” next time.

None for All

Given the proximity of each of New England’s six states to the others, it’s surprising that the place has so few regional organizations, save in esoteric fields like fly fishing and quilting. Idealists keep pressing for concerted promotion of the Northeast’s wonders, and for economic partnerships in search of new business, no matter which New England state gets the prize. Instead, each state tends to tell its own historic story, extol its own charms, and lay out its own case why it, above the others, offers the most authentic New England experience.

|

| New England isn’t paradise, but it has its allurements, including sunsets like this one over Nantucket Island |

***

A Chill in the Air

Changing gears: Last time, I told you that President Barack Obama was quite a “city fella.” This week he showed that he’s a hardy one, too.

|

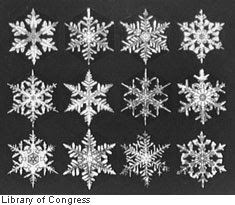

| These are forms of snowflakes, the most dreaded sight in Washington, D.C. |

The weather forecast for Chicago on Friday, the day this is posted: High -8° Celsius. Low -10°. No snow, but just wait! So far, it has been the 10th-snowiest winter on record there. Cold warriors in Chicago. Wimps in Washington.

***

Which County ’Tis of Thee?

|

| Legendary conductor Arturo Toscanini said Marian Anderson had a voice heard “once in a hundred years" |

This year, young performers Josh Grobin and Heather Headley sang “My Country ’Tis of Thee” at the inaugural concert. Then Aretha Franklin, who’s known as “The Queen of Soul,” sang the tune – whose actual title is “America” but is better known by its first line – just before Obama took the oath of office.

Listening to all three performances, I realized that many, many Americans – myself included from time to time – forget (or do not know) that the musical score of “My Country ’Tis of Thee” is that of the longer-standing, and more famous, national anthem of Britain: “God Save the King.” (Or “Queen,” depending upon who’s on the throne.) I was curious how that song morphed into one about our “sweet land of liberty” across the pond, since that liberty was won at the hands of His Majesty’s government in London.

In 1832, Samuel Francis Smith was a theological student in Massachusetts when a friend asked him to write lyrics to some music the friend had found in a German school songbook. Though Smith could not read German, he could tell that it was some sort of stirring, patriotic tune. Even though “God Save the King” had already been adapted to other “God-saving” purposes in the young United States – “God Save the President,” for instance – Smith apparently never made the connection to the British anthem.

link to read the lyrics, and hear the tune, of “My Country ’Tis of Thee.”)

Later in 1832, the new song was first performed at an Independence Day rally – no doubt doubling the indignity for the Brits, since it was they from whom our independence was won.

It would be 99 more years before the United States got our own official anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.” In the meantime, “My Country ’Tis of Thee” served as the informal anthem on many occasions.

As beautiful and popular as it is, and as inspiring as are Smith’s lyrics, his song never stood a chance of becoming the official anthem. Can you imagine the band striking up “God Save the Queen,” followed by “My Country ’Tis of Thee” at a big British- American sporting event?

TODAY'S WILD WORDS

(These are a few of the words from this posting that you may not know. Each time, I'll tell you a little about them and also place them into a cumulative archive of "Ted's Wild Words" in the right-hand column of the home page. Just click on it there, and if there's another word in today's blog that you'd like me to explain, just ask!)

Alacrity. Quickness or eagerness. Someone who is offered the last remaining ticket to a sold-out concert would be wise to accept it with alacrity.

Codgers and Geezers. Eccentric but amusing old men. The words for women who reach old age appear to be less forgiving.

Dour. Brooding or glum. One with a dour disposition isn’t enjoying life at the moment. By the way, the word is pronounced “DOO-er,” not “DOW-er,” for reasons that escape me.

Endemic. Present at all times in a country or people. Cheerfulness, for instance, seems to be endemic in the Caribbean Islands. The word also has a medical meaning, referring to the incidence of disease in a population.

Gargantuan. Really, really big! This would be a great word to apply to a huge monster in one of those Japanese films: “Godzilla Meets Gargantua.”

Hardscrabble. This word almost defines itself. It’s an adjective referring to a place that’s difficult to work or make money from. And thus, those stuck there have a hardscrabble existence as well.

Soubriquet. A familiar, rather than formal, name, often applied to a person. Thus, parents will call their son James “Jim,” and Jim often becomes “Jimmy.” It’s pronounced SOO’-bri-kay, after the French.

Snippet. A little piece, as if it had been snipped off. A phrase or a line would be just a snippet of a poem.

Triangle Trade. Trade among three distant regions, notably this ungodly exchange of slaves from the late 17th to early 19th centuries: Caribbean merchants would ship sugar, tobacco, and cotton to mills in New England or Europe. Those owners would ship rum, manufactured goods, and textiles to Africa. And “slavers” would send captured tribesmen as human cargo to the New World.

Please leave a comment.